Shepherds Of Uttarakhand

Among the highest and remotest landscapes of India, four types of people are usually found – soldiers, mountaineers, trekkers and shepherds.

The incessant rain had by now started seeping into my clothes. Shivering to the core, I reached a primitive campsite which had shelters made out of tarps, canvas sheets and piles of rocks. Sipping a much-needed cup of hot tea, a thunderous sound shook me while my hosts remained unperturbed. Soon, I came to know that the sound was that of an avalanche on the north face of Swargarohini. By dusk the sky had cleared and I strolled around the last shepherd camp towards Jaundhar glacier.

Crossing high passes is a way of life for the community of shepherds. Transhumance, which is the movement of livestock between different grazing grounds in summer and winter, has been practiced since thousands of years. In mountains, the movement is between higher pastures in summer and lower valleys in winter.

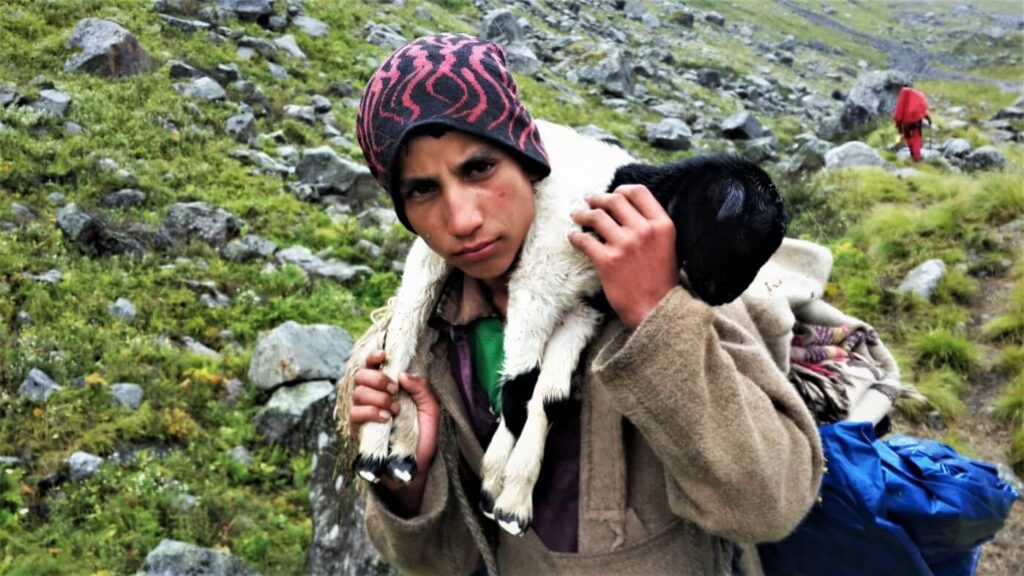

There exist a wide variety of shepherds belonging to several communities across Uttarakhand. Transhumance is practiced to varying degrees by each. Most of them follow an amalgamation of pastoralism and being able to return to their permanent village homes. For instance, the shepherds I met near Jaundhar glacier were from Osla, which is a remote village on the way to Har Ki Dun. They were a group of around eight comprising of men and teenagers. Hundreds of sheep and mountain goats formed the livestock. With their advent in the month of May, this forgotten part of Indian Himalayas was full of life again. We came to know about other shepherd groups who were in the adjacent Hata and Marinda valleys. One particular group of shepherds stays in the meadow for a few weeks. Then, some of their relatives and friends would arrive from the village and take their place. We camped there in August, about 11 km ahead of the GMVN guest house at Har ki Dun.

With the receding snow in mid-summer, the grass and herbs start turning green. This signals the migration of shepherds to higher meadows. Some of these meadows are situated well above 4,000 meters. Grazing goes on till the end of September. Soon with the brownish autumn hues taking over, the entire flocks are brought back to near the village for a brief interval. Before their native valleys are buried under several feet of snow, the shepherds move to lower parts of Himalayas. Many of us may have witnessed flocks of sheep and goats crossing roads near Mussoorie in winter. That surely creates a lot of ruckus for vehicles. But what we need to realize is that shepherds walked on these lands since way before the vehicles were invented!

Worthy of mention here are the tribes identified as Bhotias and Van Gurjars. Bhotias comprise of seven different tribal groups spread across seven valleys of upper Garhwal and Kumaon. Some of the areas inhabited by Bhotias are: The village of Bagori near Harsil (can be visited during Lamkhaga Pass trek), Mana which is ahead of Badrinath, Malari and nearby villages, Milam and Johar valley’s other settlements, villages in the Darma valley, and numerous other villages further upstream along Kali river.

Bhotias are partially of Tibetan origin. Usually, they own one set of residence for summer in a high-altitude village and migrate to another home in a lower valley before winter. Before the Indo-Tibet border of Uttarakhand closed in 1962, they were known to travel freely across the border passes for trade. From decades, parts of these communities have merged with others and migrated slowly to towns and cities. The movement has left behind some old and abandoned settlements in remote corners of Uttarakhand Himalayas.

During one of my trips to the forest area of Devban (a beautiful weekend destination close to Dehradun), I was invited by a Gurjar family to their hut. A makeshift cabin made of stones, pieces of wood and tarp served as their home. Though the arrangements were basic, the tea and smiles were warm!

Van Gurjars are Muslim communities and many of them still practice pure transhumance. In winter, large groups of Van Gurjars are settled in the forests close to Dehradun. Long have they suffered in the hands of forest and wildlife authorities. With herds of buffaloes and cows, the Van Gurjars dwelling in the land between the rivers Yamuna and Ganga, migrate to upper Tons, Yamuna and Bhagirathi valleys in summer. Since long, they have been supplying milk and milk products in the region.

On another monsoon day, I reached the village of Barsu by late afternoon. Accompanied by a mountain dog, I walked up the forest trail and reached Dayara Bugyal in the evening. A shepherd friend knew of my arrival and hosted me. His hut had all the amenities needed for a comfortable stay – a camping mattress, sleeping bags, blankets, food, water storage and last but far from least, a fireplace. His simple mobile phone was lying on one corner – the only spot where he had network (that’s how I had informed him of my journey).

During most of the Himalayan treks, we come across such shepherd huts. Kedarkantha has them on the way as well as in the basecamp. Nag Tibba’s Kathian campsite has some shepherd huts. The huts in Roopkund also served as shops and dhabas to trekkers. These primitive structures serve as their summer settlement. Trekkers often use these huts as overnight shelters or kitchen. They are mostly warmer than tents!

Since trekking comes naturally to them, shepherds involve themselves in multiple ways. It is a decent way of earning some extra money. Many of them help as porters. Some use their mules to carrying luggage. A few use their properties as homestays and campsites.

One summer evening at the campsite of Guling in Kuari PassI thought I was all alone, trekking solo and alpine. Then I remembered about someone and walked across the meadow towards the shepherd tent. We shared jokes, and stories of our journeys while watching Dunagiri peak. The man had been all by himself for over a week but surely was humble, patient and positive about life…